Tracing the Flavour of Living Heritage in Jak

By Wasantha Wijewardena and Malinda Seneviratne

|

In search of the sacred grove

Once upon a time, the world was one. It was a time when the notion of the sacred grove described not some paradisiacal place reserved for chosen people. The sacred grove encompassed the entire universe. It was a time, as the saying goes, when man had a direct relationship with the entities we now refer to as gods and Buddhas. In other words, men and women understood and lived in concert with the natural cycles. They met on the good earth, made love in caves and shady thickets, saw diversity, respected difference, and celebrated life. Endowed with a deep understanding of nature, their lives and their relationships were natural. Their practice and its outcome were benign and beneficial.

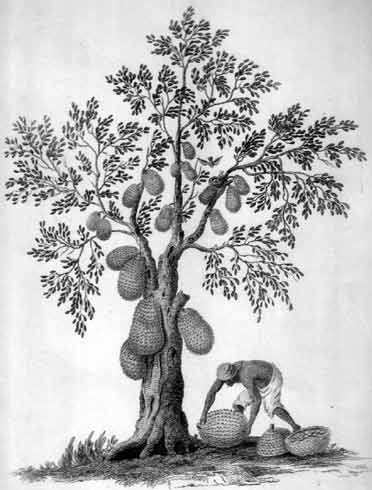

The notion of the sacred grove, or the abhaya bhoomiya (literally, “fearless land”) took a long time to disappear from the universe of human concerns. Even our kings were aware of the worth of the sacred grove. King Parakramabahu, for example, maintained a grove of 100,000 varieties of kos, or jak (artocorpus heteropilus). This was called Lakshodyanaya, the grove of 100,000 trees. He was but engaged in a simple exercise of recreating at a micro level the sacred grove.

Varaka gasa pana mal gena galeka hova

Evaka ema kalka thana kiri patheka lava

Vasaka siti ayata dee me lesa nimava

Visa vee miyena sosatha edukinmudava

This verse, which comes in the “Sarartha Sangrahaya” (Book of all meanings) is attributed to King Buddhadasa, the renowned physician and healer. Here, the poet refers to the medicinal value of kos, or jak fruit. The Mahawansa, the great chronicle written in the 4th century refers to kos. The Amavatura, the great literary work of the 12th century also refers to kos. The Visuddhi Magga, the great philosophical treatise authored by the Rev. Buddhaghosa, and the 16th century work on ayurvedic medicine, Yogaratnakaraya, too refer to kos.

Similarly, our ancient literary and philosophical works are replete with references to biological diversity, for it was not just kos that was held sacred. The “sacred grove” was also referred to as hime (the wilderness surrounding Samanala Kanda, the most sacred mountain in the island), sanhinda (that which heals), and deiyange adaviya (land of the gods). Similarly the words arama, arana, thapo bhoomi, etc., refer to notions of the sacred grove, refuge, place of meditation, etc.

Anuradhapura, a city which was the capital of the Sinhala kings for over 15 centuries, was a prime example of sustainable city planning. It was in fact a garden city where huge tracts were reserved for meditating bikkhus. The Mahamegha Udyanaya, (garden that attracted the great rains) gifted to Arahat Mahinda was the centre-piece of that jeweled city.

The sacred grove, even when the idea was in decline, was something that not just kings, but ordinary people too could recreate. This is the secret of the wonderful species diversity found in the gardens of the most humble of households. Panchavati, for example, refers to a grove of five different kinds of trees. It is also a term used for the sacred grove.

It was a time when food security was ensured and the emotional relationships were secure. People knew the forest intimately. They did not fear the darkness, they did not fear the forest. Therefore they did not set fire to the forest. They knew the life-giving character of the forest. This is why they called the forest abhaya bhoomi. There was the forest, there were trees, there was fruit and there was food. There was no malnutrition.

It was also a time when the book, the priest and the church were nonentities. The scientist had not yet been invented. Or patented. Thank god (note the lower case ‘g’)! What we had was the sacred grove. It described the unity of things, the unity of our inner beings with the rest of the universe in all its rich diversity.

It was a world where greed, over-indulgence, over-consumption and over-anything was absent. There was contentment. The elephants, the tuskers, the trees and vines, the rivulets, streams, waterfalls and rivers, and the butterflies too, were partners, common beneficiaries and in fact companions on a sacred pilgrimage. This is why even today, we say that the butterflies go to worship at the sacred mountain, and it is said that the elephants too, respectfully kneel at the footprint of the Buddha at Samanala Kanda or Śrī Pada, the greatest of the sacred groves.

It was nothing less than a narrative of a pilgrimage. We called it karuna karanawa, or “performing kindness”. Then it was a life practice. Today it is a ritual, and yet, one which speaks of a different ordering of the world, which is not necessarily beyond recapture.

All this is of course beyond the understanding of “modern man” whose imagination is hampered by the book, the teacher, the priest and the scientist. It is beyond the grasp of the postmodernists too, for the mere prefix “post” indicates a fundamental fascination with linear time: they cannot understand timelessness.

What has all this got to do with kos? Just this: this is an ancient story about ancient traditions. More accurately, this is a journey in search of those traditions. All such pilgrimages begin with the planting of a milky branch of the kos tree. We called this kapa situveema. Therefore we begin with kos. It is, after all, the symbol of a sustainable universe, said to last as long as the sun and moon exist and not least of all, because it is said that its seeds were the first foods of the most ancient of our ancestors.

This is therefore a story of stories. One might think, and not without cause, that it is about the jak Fruit. But that would not be totally true. This is a story about simple things like the pleasures of delicacies that titillate the taste buds. It is about the games that children play. It is also about things that some people think are serious, like life, famine, food security, shelter, ecological balance and sustainable livelihoods. And then, as our ancients would say without really saying the word, it is a philosophical story.

| Living Heritage Trust ©2020 All Rights Reserved |