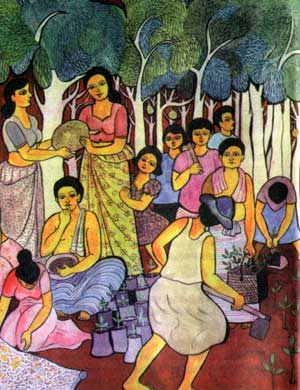

Jak fruit in Sinhala culture

Jak, pulsating in the language of social life

|

|

|

by Wasantha Wijewardena and Malinda Seneviratne

It is universally accepted that life is intrinsically linked with the sun and the moon and the processes they describe and provoke. This is why the most ancient peoples of the earth (and in fact the most environmentally conscious) worship the sun and the moon as divine entities.

The seed was in the womb of Mother Earth. When the Adi Buddha, or, in more conventional terms, the first being endowed with the faculty of awareness, descended on the earth after many centuries journeying from tree to tree, took these seeds as food. Among all these seeds, the Adi Buddha discovered jak. This is why we, who are the descendents of the long line beginning from Maha Sammata Manu, use a lactating branch to launch the perahera or procession of the Sacred Tooth Relic in Maha Nuwara.

Ekanayake Mudiyanselage Heenbanda, the family elder of Koswattegedera (House of jak, situated in Gannoruwa where the battle to rid the country of Portugese began), whose family has traditionally provided the branch of a jak tree for this ceremony opines that it is doubtful if the related customs are being properly observed and believes that the current crisis in the country is simply due to this negligence of sirith or custom.

The Adi Budu story we mentioned above was related to us by Veda Gedera Ousadahami Atha. We tend to respect and believe our elders. However, if a scienticised version of this story is required, we strongly recommend a close reading of Shiran Deraniyagala’s work on the early inhabitants of this island.

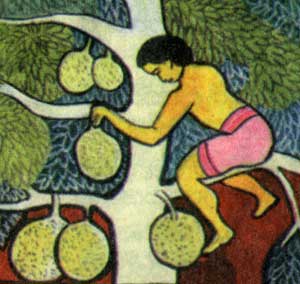

Shiran Deraniyagala, eminent archaeologist and Director General, Archaeological Department, maintains that the Balangoda Man (homo sapien balangodeinsis), the earliest human found so far on this island (found in Batadomba Lena, Kuruvita) had used bedi del eta (Artocarpus nubilis, a wild variety of jak) for food.

But jak is not just something that only our ancestors used. There is ample evidence in place names and in the Sinhala idiom to show that jak is intrinsically linked with our cultural ethos and way of life. Furthermore, the legends associated with the Pada Yatra (march on foot) from Mullaitivu to Kataragama, as described above, show that jak is connected with the notion of an integrated polity cutting across all ethnic groups.

Kos has etched its living, cultural signature in every corner of the island, if not through place names, then through its significant presence in idiom and legend.

There are many stories related to the jak fruit tree. There are many verses that were sung to the raban (an instrument similar to a drum, but normally played by a group sitting around it) beat during the Sinhalese and Tamil new year season in April every year regarding to the jak trees.

“Heralith kaththira maduluth kos eta irida

Pitos katu sivilla

Duppath thaleta-ath dena kemathi

Meke anith eka gahapalla”

Thus would sing one group, describing the jak fruit, requesting in the last line that the other group responds. And they would sing:

“Thana kola ahurak mitata kadagena- indah!

indah! Kiyathey

The they they, indah! indah! kiyathey

kos katu kulak kare thiyagena-galata kittu

vethey

Madu kola galak mitata kadagena- indah!

indah! kiyathey.

The they they, indah! indah! kiyathey

Ran patak gena kare damagena – kanuvaka gos

bandithey

The they they, the they they

Mechchara me rata pirimi sitiddith- genu

harak bandithey.

Here they relate the story of a woman feeding her cattle with the thorny covering of the jak along with a bundle of grass. Cows, it must not be forgotten, are frequently fed jak leaves. And it is not just the cows, elephants too, especially those in captivity, are fed with jak leaves:

“Kande kaka lande yana bosattu

Atapa mini payapa mini bendagattu

Raja saben sonda karuna lebagattu

Walawe gangata bessai gomara eththu”

This refers to captive elephants, who were treated with the respect due to a bodhisattva, who climbed from the sacred mountain, Śrī Pada down to the Walawe River via Koslanda. Koslanda is said to be the birthplace of elephants. Over two thirds of the villages that have “jak names” happen to be in and around the plains of Koslanda. It is also in this area that Kosgama Kiriamma, the woman of Kosgama Atapattu referred to above, is worshipped. There is also a Vatarappali Amman Kovil in Putramalai, Haputale.

The place names that contain a reference to jak can be rattled off like the lines of a rap song. Kosgama, Koslanda, Kosgoda, Koswatte, Kosmulla, Kospitiya, Kosgamawewa, Kosgammulla, Kosgolla, Kosgahakumbura, Kosgahatenna, Kosgahamulla, Kosgahamankada, Kosgolletenna, Koskabale Ela, Kospolamulla, Koskanuwa Amuna, Kosgahauhana, Kosgahaarawa, Warakawa, Warakapola, Warakadeniya, Warakawa, Warakaulla, Panawala, Panawenna, Panamure, Panapitiya, and Panamaldeniya are some of these. Today place names are derived from the names of politicians. The ancients named places after living, beneficial, identifiably, and unambiguous things. Like trees.

Language, as any social theorist would say, is not just a channel of communication, but a vehicle of living culture and more importantly, it is a transcript of social intercourse. When things enter the fascinating world of metaphors, then it is clear that they are inextricable and healthy parts of not just social interaction but a world view too. Our ancestors were blessed with the proverbial third eye. They talked not just words, but words so painted with real, live things that they were “One with nature” without having to theorise the fact nor strive to live it. There are probably hundreds of phrases, proverbs and idioms associated with jak. The following are a representative sample gathered from all parts of the island.

“Hariyata meka kos kanda vagei” (He is like the trunk of the jak fruit tree) is a reference to physical strength. “Meka hariyata kos etayak vage” (He is like a jak seed), alternatively, refers to somehow who is small made. Interestingly, the kos metaphor is used to ridicule as well. “Meka thama eten sividden penneth nae” (He has not yet jumped out of the seed and the casing), derides a boy who refuses to act his age.

Someone who is extremely skilled would invite the following observation:”kos gahe mulin gihin agen bahiy”; he could start at the root of the jak tree and get off from the edge of a branch. Sometimes, when one is in a foul mood, others would respond thus: “Moona hariyata kos gediya vage karagena”; the face is swollen and sullen like a jak fruit.

“Yako koholla vage elennethuva hitapanko” (Don’t stick as though you were a bit of jak latex) would take issue with someone who is overly friendly or sticks to one like a leech. On the other hand, it is also said, “Kosuy poluy vage” ([they] are like jak and coconut; meaning they complement each other well). Similarly, “Koseta nam maru karavala katu hodda” (A dried fish curry ideally complements jak fruit) also talks about things or people that go together.

| Living Heritage Trust ©2020 All Rights Reserved |