The Jak fruit and fertility

by Wasantha Wijewardena and Malinda Seneviratne

|

|

We all know that it is the sun that provides us with energy. In Sri Lanka we always talk of a sustainable mode of being that is described in the vast time frame symbolized by the caveat, ira handa payana thak kal, while the sun and moon exists. The good earth was always pregnant with seed. Jak was one among the many seeds she carried in her bountiful womb. It is said that the Adi Buddha, upon reaching some level of realization, set foot upon the earth. Being the mother, the earth had welcomed him warmly and with utmost love and fed him the bedi del eta, the jak seeds. We are but the descendents of the Adi Buddu or the Manu of the Maha Sammata, the Great Consensus.

The most ancient of the ancients dwelled on the idea of fertility. Wisely so, we might add. Today there seems to be a fixation about progress. Community is broken and its dislocated parts today follow what we prefer to call “The ER Ethic”. Today it is about being better, richer, smarter, bigger etc. And so we are trapped in the unreal world of poverty whose numbers can be manipulated with a deft redefining of poverty lines and thresholds.

Back then it was about prosperity and, more pertinently, the prosperity of a community. Our ancestors thought about the varige, sanhathiya, sanuhare, and the gama. In other words, about the collective. Although large numbers were not tossed around sophisticated equations, although grandiose terms were not hotly debated and deftly employed in dissecting social process, they knew the importance of the simple things in life. This is why they talked about being prosperous in terms of the proverbial bathaand bulatha, i.e, rice and betel. This is why they talked of life overflowing with milk and honey.

Since this was integral to the collective ethos, all sacred ceremonies were started with the planting the branch of a lactating tree. Hence the association of the jak with the sacred.

Prosperity and fertility are things that go together. In the great understanding of the ancients they were not separate, but one. The Orient has a long history, and one, which is resident in folklore, customs and belief systems, of worshipping what for the sake of convenience, is referred to as the Mother Goddess. Depending on place and age, the Mother Goddess was named and re-named, but her essential rhythms and life force and the perception of these in the eyes of the believers remained the same. Called Jagan Matha, Mahee Matha, Tara, Kali, Lakshmi, Sita, Pattini, Kannagi, Parvati, Madu Matha and Santhanam Meniyo by different people in different places, the name was always associated with the earth, timely rains and sunshine, and fertility, and the cyclic character of the natural world. In all the rites and practices associated with the Mother Goddess, two things were apparent. One, sensitivity to the natural rhythms, and, two, the transferring of such wisdom from generation to generation. Both these were symbolically represented in sacred ceremony. In this island, the perahera, the kariya, the maduwa, yakkama, tovilaya, baliya, yagaya, kem pahan, sanni dance, etc.

Let us now go to the Mullaitivu jungles, to be more exact, in the sacred precincts of the Vatarappali Amman Kovil, from whose bosom begins one of the several journeys that brings our people together and bind them to each other as a community.

The pada yatra (foot pilgrimage) associated with the Vatarappali Amman Kovil is known as the Kataragama Pada Yatra, since Kataragama is the destination of the long march that begins at this kovil, a march that has a history of over a thousand years. It is indeed a living tradition which indicates that never was there a separation of this island least of all along ethnic or religious lines.

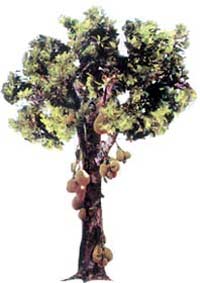

What has all this temple stuff and marches got to do with jak? Simply this: the main offering at this kovil is peni waraka and has been so for centuries with people from all over the country and even outside the island journeying long distances to make these offerings. This is part of the reason why we refer to jak as the Kalpa Wruksha (Tree of Eternity) or Jeevana Wruksha (Tree of Life). In fact the annual sacred ceremony held in every temple in the island, in which a perahera usually takes place, is ceremoniously launched with the planting of a branch of the jak tree, referred to as the kapa situveema. This is also done whenever a house or any other building is put up. And when a young girl attains age, she is taken by her mother or an aunt to a jak tree where she gives a blow at the trunk with a sharp knife, making the white milky latex ooze, once again symbolizing prosperity.

Back to Mullaitivu. Even today, there is an extensive glade of jak trees surrouding the Vatarappali Amman Kovil. The many varieties speak to the many peoples that have over the centuries made offerings here.

Yes, we almost forgot, all this is not just about some petty human ceremony. One cannot forget those insightful words of Eliot after all: “A religion requires not only a body of priests who know what they are doing, but a body of worshippers who know what is being done”. In addition to desperate people wanting to bribe the gods and equally suspicious kapuralas (priests) standing in for god, there is rich animal and bird life in the area to whom the gods have bequeathed, without even a single offering other than that of living according to the dictates of nature, a succulent and nutritious source of food. And of course shelter.

So, both symbolically and physically, the jak is symbolic of the Mother Goddess, the source of fertility and life. There is a popular Tamil saying which goes like this: “Andamam pundamam seyrandi; abhilamba kodi sarasaram.” It speaks of life beginning when the seed of the jak enters the womb of Mother Earth. Need we anything more about jak, fertility and prosperity?

| Living Heritage Trust ©2020 All Rights Reserved |